|

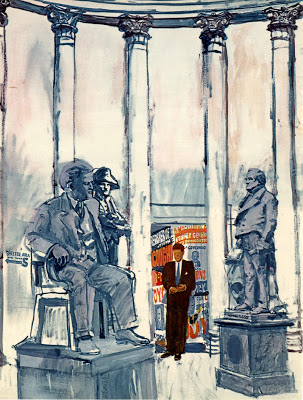

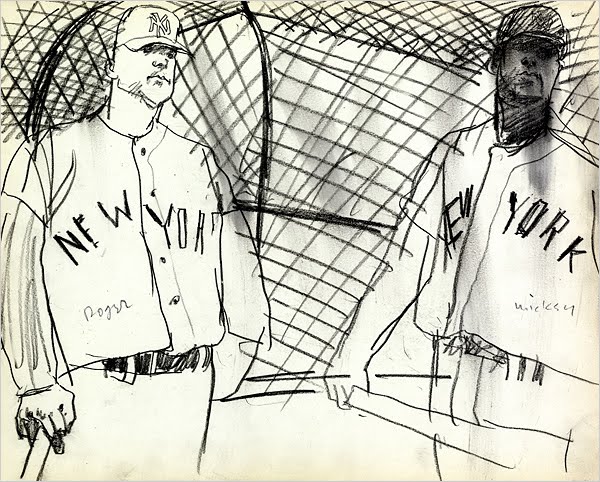

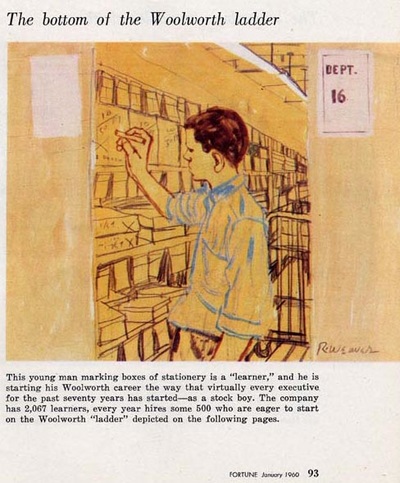

Fig 1. Robert Weaver. Kennedy's last chance to be President. (1959) Esquire Magazine. Robert Weaver is one of the great visual journalists. He was passionate about drawing from life, and was influenced by contemporary young artists and film makers such as Ben Shahn and Roberto Rossellini. Weaver believed that Art and Illustration were very closely allied, and sought to include personal expression, comment and content-full narratives into his work. This attitude really changed the perception of illustration practice in 1950's America, when most illustrators were considered craftspeople, commercial artists who decorated, but didn’t comment. There's a background to the emergence of illustrators like Weaver. When television arrived in more and more homes, it began to siphon off advertising revenue, so magazines, dependent on their money, were left with smaller budgets, and more pages to fill. In addition, the late 50’s and 60’s were a time of major political and social upheaval in America. Weaver identified with the idealist ‘new frontier’ politics of Jack Kennedy and with the youthful optimism of post war America (fig1). “Robert Weaver was Jack Kennedy, and the old guys were a bunch of genial but corrupt Eisenhower’s” (Dowd 2008). In the Art world from the early 1950’s, contemporary painters were embracing abstract expressionism. Figurative work was unfashionable, and painting was about the act of painting. As the decade progressed, Pop Artists back-lashed against this intellectually elite practice and painting started to reference comics, adverts, and graphic design. It was inclusive, accessible, and its narrative was about real lives and popular culture (Heller, Arisman 2004 p.43) Weaver drew on the expressionist aesthetic, using colour as an emotive tool, with broad expressive strokes of paint. He juxtaposed elements of story in multi layered composite drawings, using graphics, posters and typography to contextualise and inform. It is no accident that alongside books, websites and other resources devoted to visual journalism in the 60’s, you’ll find the names of the Art Directors who commissioned them. These men and women gave Weaver and his contemporaries the space and the freedom to investigate and draw what they saw in the world. They were trusted to fill sometimes up to eight pages in an issue. Leo Linni who worked for Fortune magazine 1948-1960 sent Weaver to illustrate an article entitled “What’s come over old Woolworth?” (fig 3). Weaver sketched on the spot, a hierarchy of employees, starting with the Stock room boy all the way to the board members. He barely altered the illustrations for print except to wash over with colour. Richard Gangel, Art Director for Sports Illustrated, regularly commissioned Weaver, including 'Spring training', an iconic series of Baseball players published in 1962 (fig 2). Others include Robert Benton and Henri Wolf at Esquire, Charles Tudor at Life Magazine and Cipe Pineles, Art Director at Conde Nast. Without the vision of these people perhaps illustration wouldn’t have developed in the way that it did. Fig 2. Robert Weaver. Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle (1962) Sports Illustrated What we need today are some more visionaries: In an ideal world, where power is back in the hands of Art Directors, who aren’t scared or too hand-tied to commission, and who see a value in the voice of the illustrator. There’s not much money that’s true, but there’s a lot of space in a digital news story (I really like how Matt Whilley and his team at the New York Times are presenting stories). On the other hand, Robert Weaver might have something, allying himself with Fine Art. Maybe producing a set of beautifully printed illustrations, which inform, comment and shed light on a subject in a new way would be something worth keeping. I’ll steal Benjamin’s idea of the 'aura’ here, and suggest this as an alternative reason to commission. Fig 3. Robert Weaver. What's come over old Woolworth? (1960) Fortune Magazine The chairs get more and more elaborate as you go up the corporate ladder. Art Directors Club (1980) Henry Wolf. Available at: http://adcglobal.org/hall-of-fame/henry-wolf/ [Accessed 12 December 2016] DOWD, D. (2008) Super Tuesday: Robert Weaver’s Kennedy suite.[online].Available at: http://ulcercity.blogspot.ae/2008/02/super-tuesday-robert-weavers-kennedy.html [Accessed 12 December 2016] HELLER, S. and ARISMAN (2004) Inside the business of Illustration. Allworth Press. New York ZALKUS, D. (2012). Visual Journalism; the Artist as Reporter - Part 2.[online]. Available at: http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.ae/2012/05/visual-journalism-artist-as-reporter.html [Accessed 12 December 2016] ZALKUS, D. (2012). Visual Journalism; the Artist as Reporter - Part 1 [online].Available at: http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.ae/2012/05/visual-journalism-artist-as-reporter.html [Accessed 12 December 2016] 14/11/2017 04:50:31 am

Journalism is not easy jobs and they get the proper education of it. But it also this job the genius person for do it this job and a honest person need of this profession. A journalist gives the articles for the political parties. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed